What separates a biotech startup that raises a funding round from another team with an equally strong idea that doesn’t?

Often, the difference shows up early: one team can demonstrate how the idea is validated in practice – through a working prototype, early technical evidence, or a clear Proof of Concept – while the other is still explaining the idea in slides.

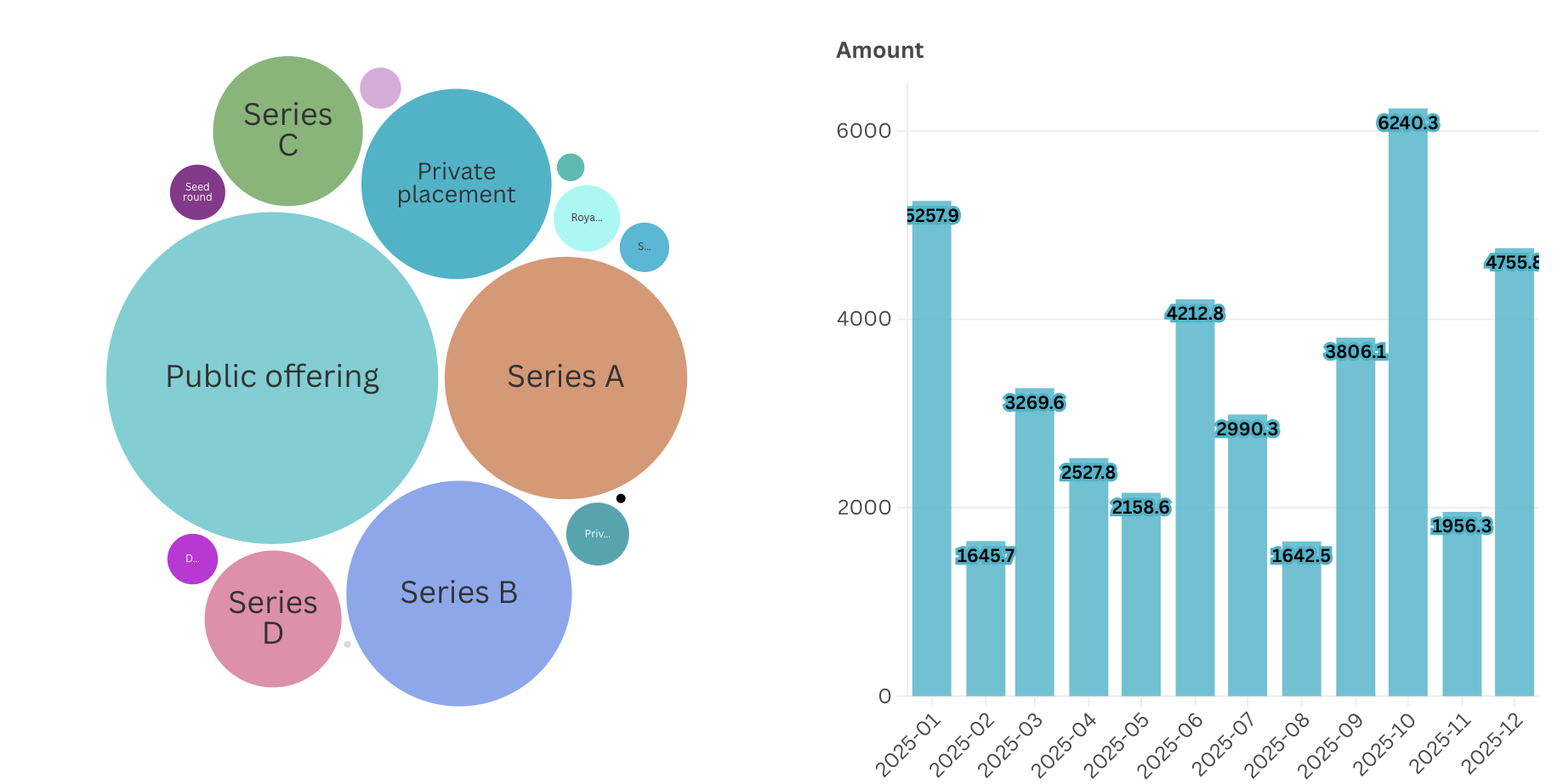

Slides have largely stopped working: the number of funding rounds has fallen to its lowest level since 2020, and deals have become less frequent despite growth in total funding volume (C&EN).

In this article, we examine what truly makes a PoC investor-ready, why traditional metrics are insufficient, and how to build a PoC that can withstand investor scrutiny and support fundraising.

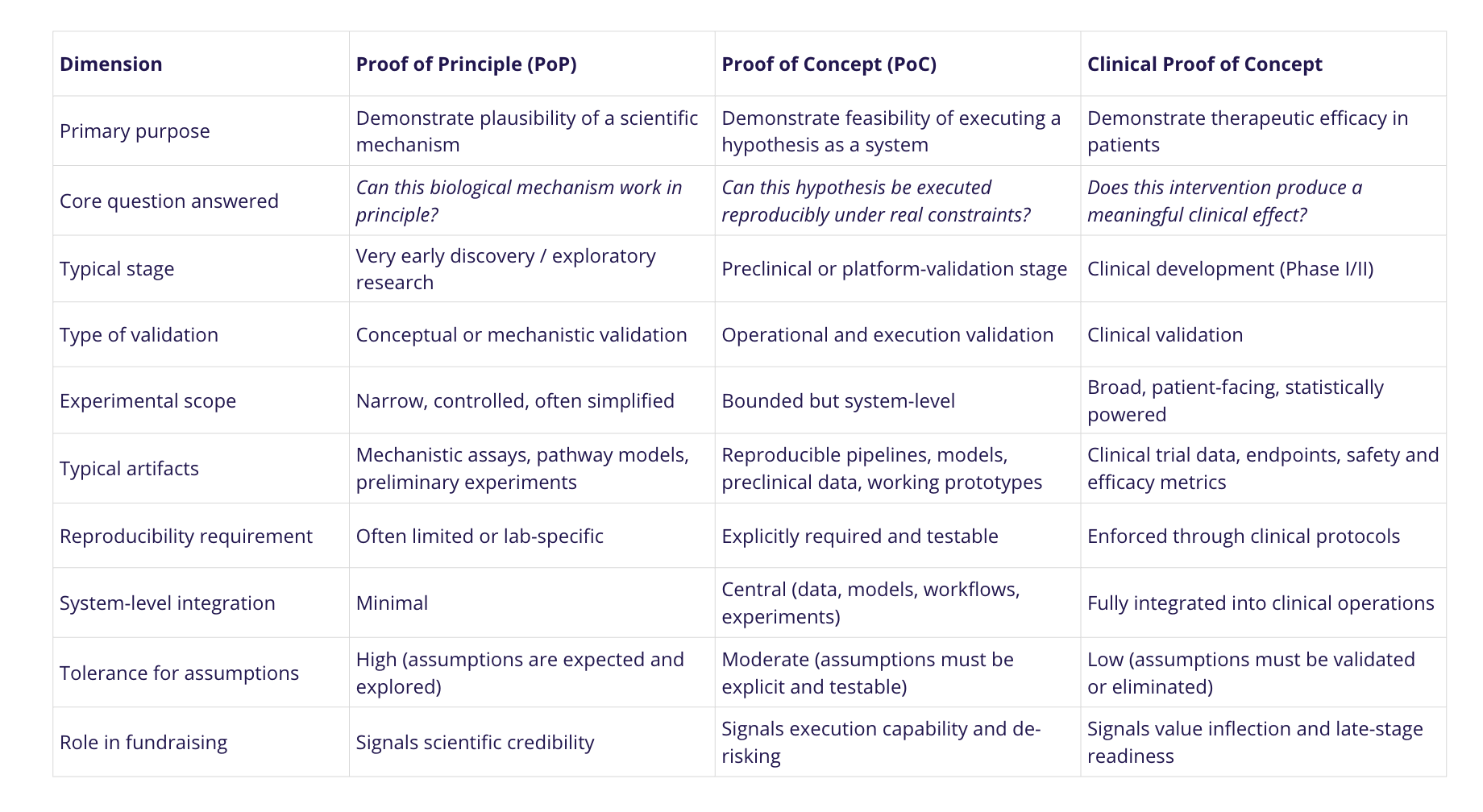

What makes a PoC investor-ready in biotech

As Bruce Booth, General Partner at Atlas Venture, has written and discussed publicly, investors look beyond the scientific idea itself and focus on whether it can be executed step by step and tested under real market and regulatory constraints – what he often describes as a clear de-risking pathway.

In recent years, funding has become more selective: overall venture capital volumes have remained significant (with tens of billions of dollars invested in platform biotechs between 2024 and 2025), but investors increasingly concentrate on projects with a clear proof of concept, detailed data, and transparent progress milestones. While substantial amounts of capital continue to flow into later-stage rounds (Series B, Series C, and public offerings), early-stage funding has become more concentrated and selective, with fewer projects advancing without strong early validation. This pattern reflects investors’ increasing emphasis on clear proof of concept, data-backed progress, and execution readiness as prerequisites for deploying capital at earlier stages. The variability in monthly investment volumes indicates that funding is no longer continuous or momentum-driven. Capital appears to be deployed in response to discrete milestones, reflecting a shift toward milestone-based decision-making where proof of concept and transparent progress act as prerequisites for capital release.

For investors, it matters that a set of testable steps – such as algorithms, models, or preclinical evidence that can be reproduced and evaluated independently of the core research. This is reflected in the trajectory of companies like Insilico Medicine, which raised more than $400 million in funding in part because its PoC demonstrated working algorithms and platform-level results.

Strong PoCs also signal commercial direction by making explicit how early technical or biological results could translate into a viable product or therapeutic pathway once sufficient funding is secured. This includes clarity on what is being developed (a platform, an asset, or an enabling technology), how it could progress through subsequent development stages, and where value inflection points are expected.

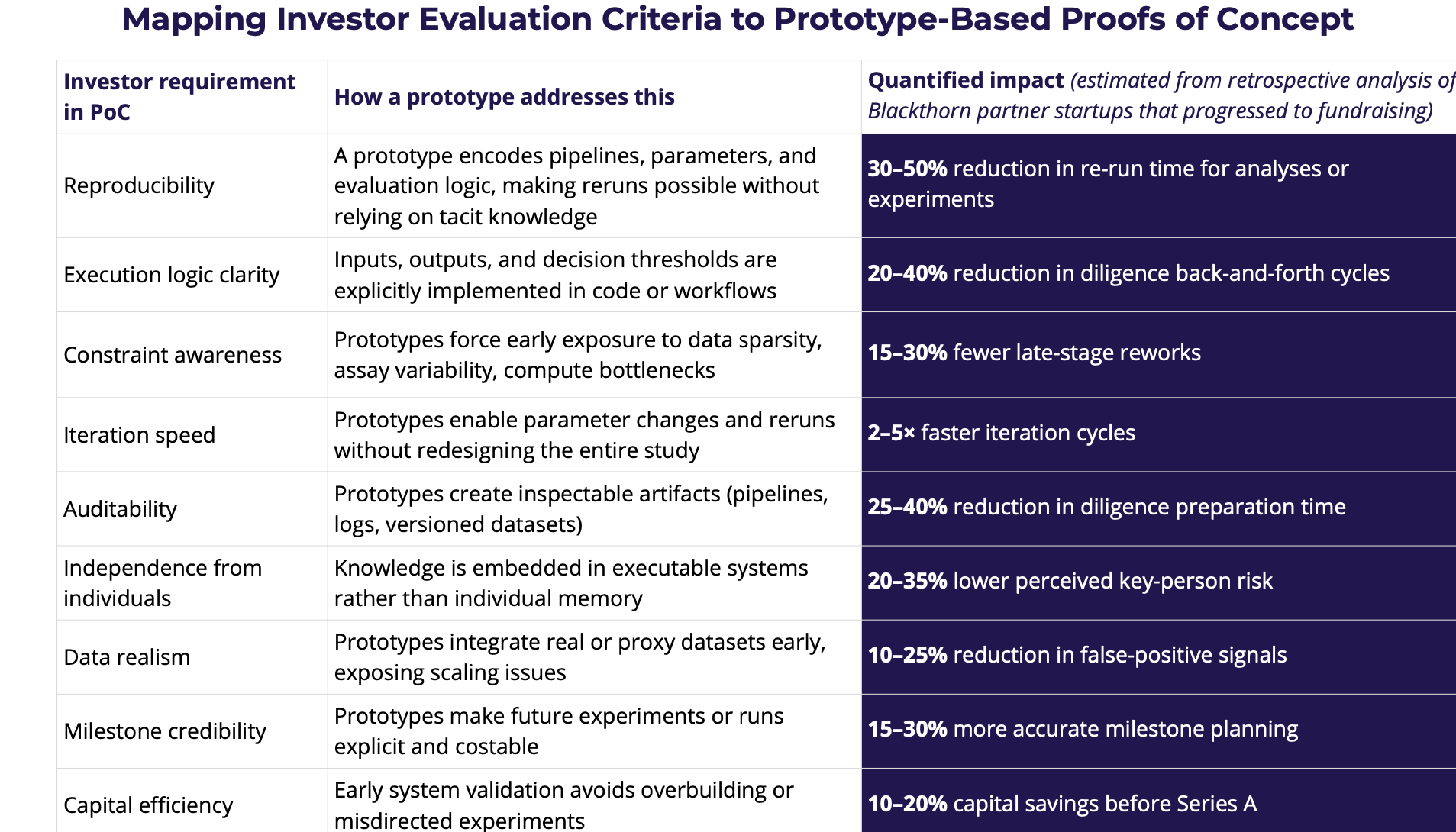

In practice, this clarity is often expressed through a working prototype that implements the core logic of the Proof of Concept. Such prototypes do not aim to represent a final product; rather, they operationalize key assumptions, making the PoC inspectable, testable, and easier to evaluate during diligence. A prototype allows investors to see how hypotheses are translated into systems, how constraints are handled, and how iteration would occur with additional capital.

An investor-ready PoC in biotech demonstrates a reproducible, stepwise path from hypothesis to evidence that can be evaluated under real scientific, technical, and regulatory constraints. By making execution logic and commercial direction inspectable-often through a working prototype-it enables investors to assess risk, feasibility, and future optionality before committing significant capital.

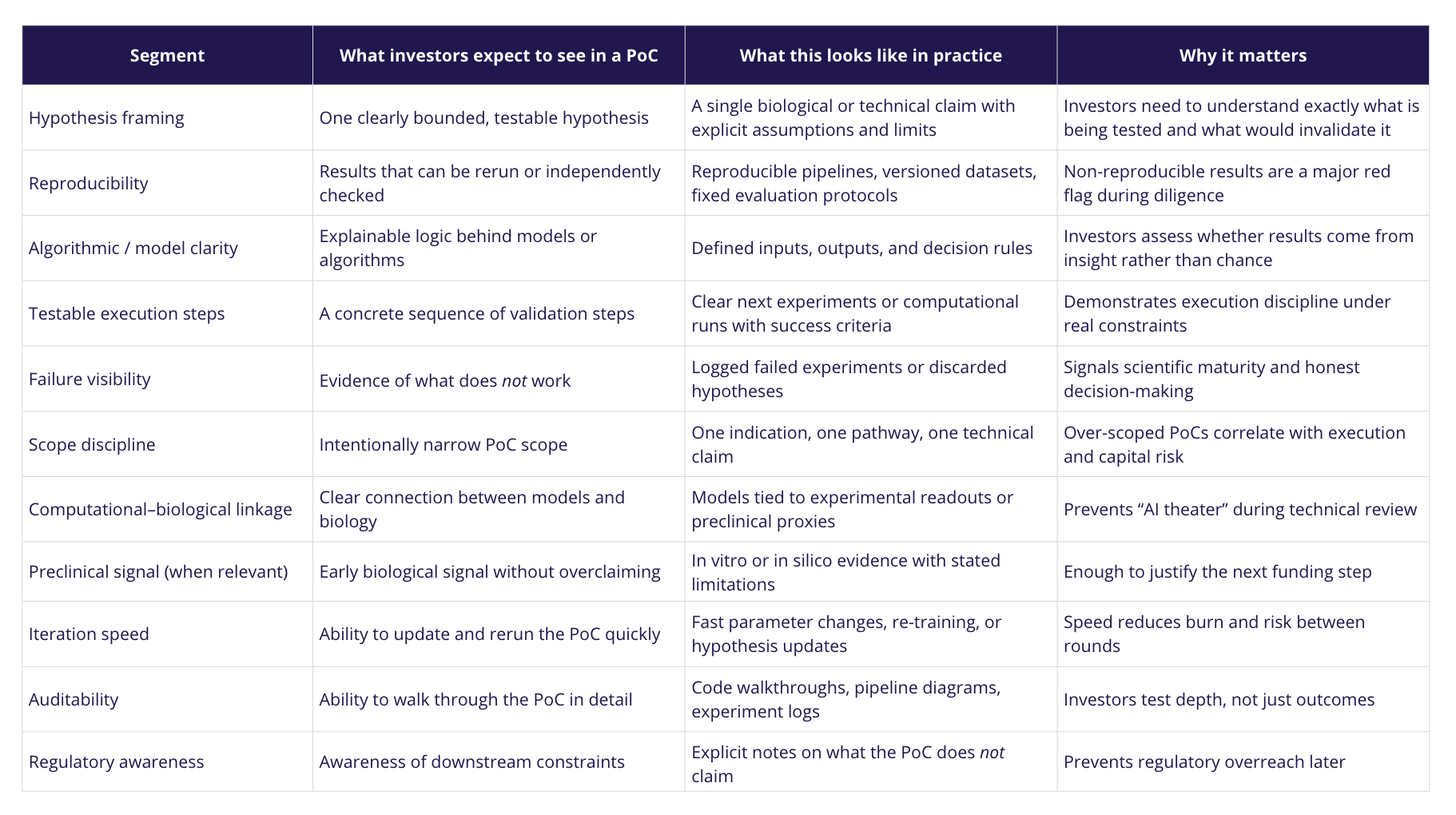

Proof of Principle vs Proof of Concept vs Clinical PoC

These terms are frequently used interchangeably in biotech discussions, but investors interpret them very differently.

A Proof of Principle is primarily scientific: it demonstrates that a biological mechanism or hypothesis is plausible, often in a controlled or simplified setting. A Proof of Concept moves one step further by showing that this hypothesis can be executed as a repeatable system – computational, experimental, or hybrid – under practical constraints. A clinical PoC, by contrast, addresses therapeutic efficacy in patients and typically sits much later in the development timeline, closer to regulatory decision-making.

In practice, most early-stage biotech companies raise capital well before reaching clinical PoC. According to industry analyses summarized in Nature Biotechnology, a majority of Series A biotech financings occur at the preclinical stage, with investors relying on preclinical, in silico, or platform-level PoCs rather than patient data. Companies such as Recursion and Insilico Medicine raised substantial early funding on the basis of computational and preclinical PoCs that demonstrated execution capability and scalability, long before clinical efficacy was established.

For fundraising purposes, PoCs therefore occupy a specific middle ground: they are grounded in science but evaluated through execution. Investors use them to judge whether a team can systematically test, refine, and advance a hypothesis – without expecting the regulatory proof required at the clinical stage.

Why a prototype is the most reliable form of Proof of Concept

At the preclinical fundraising stage, the most credible Proof of Concept is usually an executable prototype (not a slide deck, not a one-off result), because it turns claims into something that can be inspected, rerun, and stress-tested.

Investors (and their scientific diligence advisors) don’t just evaluate whether the hypothesis sounds plausible – they evaluate whether the team can execute it repeatably under constraints (data availability, assay noise, compute, timelines, regulatory boundaries). A prototype forces those constraints into the open: inputs/outputs are defined, assumptions are explicit, and the PoC becomes something another person can follow.

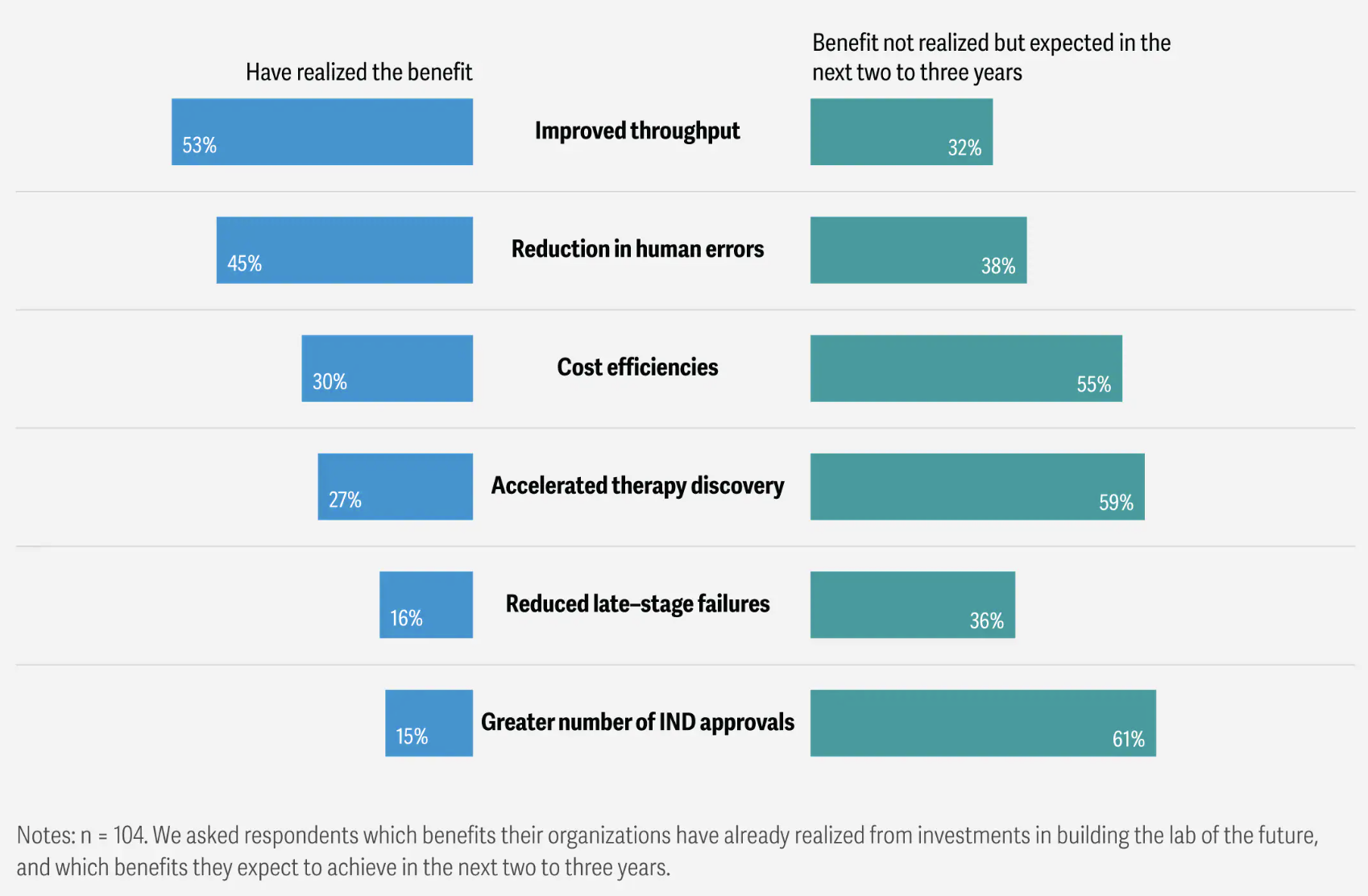

There’s also a measurable efficiency angle. A 2025 survey of 104 biopharma R&D executives found that lab modernization efforts combining automation, AI, analytics, and connected instruments were associated with operational gains: 53% reported higher lab throughput, 30% reported cost efficiencies, 27% reported faster therapy discovery, and 45% reported reduced human error. These are exactly the kinds of “execution signals” a prototype can embody: tighter loops, fewer manual errors, clearer provenance, and faster iteration.

At the PoC stage, a prototype is rarely a polished product interface. Instead, it is an executable representation of the discovery or development system, tailored to the company’s scientific and technical modality. Across biotech, three dominant prototype patterns recur.

1. Computational prototypes (platform biotechs, AI-first discovery)

In computationally driven biotechs, a prototype typically takes the form of a versioned, end-to-end pipeline that links raw data ingestion to model outputs and decision-making steps. These systems define fixed evaluation protocols, reproducible runs, and explicit ranking or selection logic, allowing both internal teams and external reviewers to assess how hypotheses are generated and tested.

Public disclosures from Insilico Medicine illustrate this model. Insilico has reported that its AI-driven platform compressed parts of the target-to-candidate timeline to approximately 12–18 months, compared with multi-year timelines commonly cited for traditional discovery workflows (Insilico Medicine press materials). Importantly, investors emphasized not only speed but the presence of a repeatable execution system, rather than isolated model results.

Similar patterns are visible at Recursion, where large-scale, automated imaging combined with machine-learning pipelines functions as a prototype of discovery execution. Recursion’s early fundraising preceded clinical efficacy data and was supported by the demonstrable scalability and reproducibility of its computational–experimental platform (Nature Reviews Drug Discovery).

Integrating multi-omics data, modeling, and prioritization logic to reduce discovery cost and iteration time.

Check how these principles are applied2. Hybrid prototypes (wet-lab + computational)

For many therapeutics companies, the PoC prototype is a hybrid system that integrates experimental assays with computational analysis. Here, the prototype consists of a rerunnable stack: standardized sample handling, defined assay parameters, quality-control gates, and analysis pipelines or notebooks that can be executed end-to-end.

Industry analyses highlight why this matters. A review in Nature Biotechnology notes that reproducibility and assay robustness are among the most common failure points identified during diligence for preclinical programs. Hybrid prototypes reduce this risk by making sources of variance explicit and by separating biological uncertainty from process instability.

Empirically, lab-automation and analytics studies summarized by McKinsey (2024-2025) report 20–40% reductions in experimental cycle times and material cost savings on the order of 10–20% when workflows are standardized and partially automated-effects that prototypes are designed to surface early, before scale amplifies inefficiencies.

By automating data ingestion, quality control, and analysis pipelines, the platform reduced manual processing by ~86% and data processing errors by ~95%, making experimental workflows auditable and scalable.

Check how these principles are applied3. Product prototypes (enabling technologies and biotech software)

For enabling technologies and software-centric biotech companies, a prototype is often a functional product core rather than a finished application. These prototypes implement the central logic of the PoC-such as experimental planning, data capture, lineage tracking, or decision rules-without full UI or enterprise hardening.

From an investor perspective, these prototypes make scalability testable. They allow diligence teams to evaluate how performance, data integrity, and user workflows behave as data volume, experimental throughput, or team size increases. This aligns with findings from venture diligence surveys reported in Nature Biotechnology, where investors cite “inspectable systems” as a key differentiator between credible platforms and narrative-driven PoCs.

At the PoC stage, product prototypes function as executable cores rather than finished applications, implementing the logic that connects hypotheses, data, and decisions. By making scalability, data integrity, and workflow behavior observable under increasing load, these prototypes allow investors and diligence teams to assess whether a platform can grow without structural breakdown. In practice, inspectable prototypes are repeatedly cited in venture diligence as a distinguishing signal between execution-ready platforms and narrative-driven PoCs.

This product prototype validates the core execution infrastructure required to operationalize AI models in regulated biotech environments.

Check how these principles are appliedTips for maximizing Proof of Concept outcomes

At the PoC stage, success is rarely determined by the novelty of the hypothesis alone. Outcomes depend on how evidence is generated, monitored, and translated into decisions under real scientific, operational, and capital constraints. The following guidelines reflect recurring failure modes observed in early-stage biotech programs and outline practical considerations that materially influence whether a PoC produces actionable signals for both science and fundraising.

1. Design the PoC for diligence, not for internal conviction

Many PoCs fail not because the science is wrong, but because the evidence cannot be evaluated by an external party. From the start, structure your PoC so that a third party can trace assumptions, reproduce key steps, and understand failure modes without relying on verbal explanation. If an investor or scientific advisor cannot independently walk through how results were produced, the PoC loses most of its signaling value.

2. Explicitly encode assumptions instead of hiding them in narrative

Strong PoCs do not minimize uncertainty-they surface it. Make assumptions explicit in code, protocols, or decision rules rather than leaving them implicit in slides or discussions. This allows investors to assess where risk lives (biology, data quality, scale, execution) instead of discounting the entire project due to ambiguity.

3. Optimize for iteration speed

At the PoC stage, speed of iteration is often a stronger predictor of eventual success than absolute performance metrics. Systems that allow rapid reruns, parameter changes, and hypothesis refinement enable teams to respond to negative results without restarting from scratch. Investors consistently view fast, disciplined iteration as a signal of execution maturity.

4. Separate biological uncertainty from process instability

A common failure mode in early biotech PoCs is conflating noisy biology with unstable workflows. Wherever possible, standardize and prototype the process (data handling, assay execution, analysis pipelines) so that variability can be attributed to biology rather than infrastructure. This dramatically improves the interpretability of results during diligence.

5. Build artifacts that survive founder absence

If a PoC only works when a specific founder explains it, it will not survive scrutiny. Treat documentation, versioned pipelines, and reproducible runs as first-class outputs of the PoC, not afterthoughts. Investors evaluate whether progress can continue as the team scales, not just whether it works today.

6. Use the prototype to define future milestones

Avoid framing the PoC as proof that “everything will work.” Instead, use prototypes to clearly define what the next experiments, datasets, or development steps must look like and what success would mean at each stage. Clear, bounded milestones increase investor confidence more than optimistic long-term projections.

7. Choose execution partners as carefully as scientific collaborators

Finally, PoC outcomes are tightly coupled to how they are built. Teams that lack in-house capacity to design, implement, and iterate executable prototypes risk spending months generating results that cannot be validated or reused. Selecting partners who understand both scientific constraints and system-level execution can dramatically compress timelines and reduce wasted capital-especially when speed and clarity matter more than completeness.

Taken together, these considerations make clear that PoC success depends as much on execution infrastructure as on scientific insight-an insight that increasingly drives how biotech startups select partners for rapid prototyping and early validation.

Selecting partners for Proof of Concept

Deciding how to execute a Proof of Concept-whether in-house, outsourced, or through a hybrid model-is a strategic choice shaped by resources, expertise, timelines, and the nature of the scientific risk being tested. There is no single optimal model; instead, successful biotech teams assemble complementary partners aligned with the specific objectives of the PoC.

Conducting PoC work in-house offers direct control over experimental design, data ownership, and confidentiality, while enabling teams to accumulate institutional knowledge that compounds over time. However, building and maintaining the required infrastructure-cell culture facilities, animal models, analytical platforms, data systems-demands significant capital and operational focus. For early-stage startups or academic spinouts, these demands can divert attention away from core scientific questions and delay critical validation milestones.

As a result, many teams rely on external partners to accelerate PoC execution. Contract research organizations (CROs) commonly provide integrated preclinical pharmacology, PK/PD, bioanalytical, and translational services, offering access to specialized models and assays that would be costly or impractical to develop internally. When used selectively, CROs can improve data quality, compress timelines, and reduce fixed overhead-particularly when internal expertise or capacity is limited.

In practice, most biotech companies adopt a hybrid approach. Foundational experiments and hypothesis framing are often retained in-house, while more advanced in vivo studies, specialized pharmacology, or large-scale screening are outsourced. This allows teams to maintain scientific ownership while flexibly trading off cost, speed, and rigor through external expertise. Such hybrid models are widely used to support informed go/no-go decisions, portfolio prioritization, and downstream development planning without compromising scientific quality.

Alongside wet-lab and pharmacology partners, an increasingly important category of PoC partners focuses on execution systems-computational pipelines, data infrastructure, and prototypes that make PoCs inspectable and reproducible. These partners do not replace scientific validation; instead, they help translate hypotheses, experiments, and data into executable systems that investors and diligence teams can evaluate.

For biotech teams where validation depends on showing how a hypothesis is executed, prototype-backed PoCs can shorten time to validation and improve fundraising readiness.

Book a ConsultationConclusions

As funding markets have grown more selective, investors increasingly rely on PoCs that demonstrate reproducible, stepwise execution under real scientific, technical, and operational constraints, rather than narrative explanations or isolated results.

Proof of Principle, Proof of Concept, and Clinical PoC serve distinct functions along the development timeline. While Proof of Principle establishes mechanistic plausibility and Clinical PoC validates therapeutic efficacy in patients, fundraising PoCs occupy a middle ground: they translate scientific hypotheses into executable systems that can be independently inspected, rerun, and stress-tested without requiring regulatory-grade clinical evidence. This positioning explains why most early-stage biotech financings occur at the preclinical or platform-validation stage.

Across multiple investor criteria-reproducibility, auditability, iteration speed, and risk de-risking-executable prototypes consistently emerged as the most reliable form of PoC. By encoding assumptions, constraints, and decision logic into inspectable systems, prototypes convert abstract hypotheses into artifacts that diligence teams can evaluate directly.

We further demonstrated that PoC prototypes take different forms depending on modality: computational pipelines for AI-first discovery platforms, hybrid wet-lab–computational stacks for therapeutics programs, and functional product cores for enabling technologies and biotech software.

Finally, we outlined practical guidelines for maximizing PoC outcomes, emphasizing diligence-oriented design, explicit assumption encoding, rapid iteration, separation of biological uncertainty from process instability, and the strategic use of partners. Effective PoC execution rarely relies on a single organization; instead, successful teams combine internal scientific ownership with external partners who provide specialized assays, infrastructure, or execution systems.

Taken together, the evidence supports a clear conclusion: in contemporary biotech fundraising, the strongest PoCs are not defined by completeness or polish, but by their ability to demonstrate disciplined execution. Executable prototypes are the primary mechanism by which early-stage teams convert scientific potential into investor-grade evidence, enabling capital to be deployed against measurable progress rather than narrative belief.